Investigating the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Through the City Cemetery

by Phoebe R. Stubblefield, Ph.D., F-AAFS

Director of the CA Pound Human Identification Lab, University of Florida

In May 1921, a young African American man, “Diamond” Dick Rowland, was arrested for allegedly assaulting a white female elevator operator. Thanks to a newspaper article published by the Tulsa Tribune on May 31st, a white mob formed outside the courthouse where Rowland was jailed. Representatives from the adjacent Black community of Greenwood repeatedly approached the sheriff offering support to maintain rule of law for Rowland, and after one of these visits someone in the white crowd accosted a Greenwood resident, shots were fired, and several men were injured or killed that night.

The next morning an organized white mob entered Greenwood and systematically looted, burned, and incarcerated the residents. For a detailed history from an eyewitness, I recommend Mary Parrish’s book, Events of the Tulsa Disaster, or in its modern title re-released by her granddaughter, The Nation Must Awake. Almost forty blocks of Greenwood were destroyed, and the number of deaths was under-documented.

In 2000 the state of Oklahoma appointed a commission to investigate whether there had been a race riot, memories being short, and my late colleague Dr. Clyde Snow assembled the majority of death certificates associated with the event. Deaths of those shot on May 31st were certificated, even if they died months later in hospital. Thirty-nine male deaths, black and white, were recorded, and about twenty black men were buried June 2nd in unmarked graves in Section 20, the Colored Potters Field of the city cemetery, Oaklawn. Markers for two victims, Reuben Everett and Ed Lockard, had been placed at some point, and this location was dubbed the “Original 18” area, based on the assumption that the other 18 males were buried nearby. However, no further action occurred, and in 2018 Tulsa mayor GT Bynum undertook the recovery, so that no individuals killed in the event would continue buried hidden in anonymity.

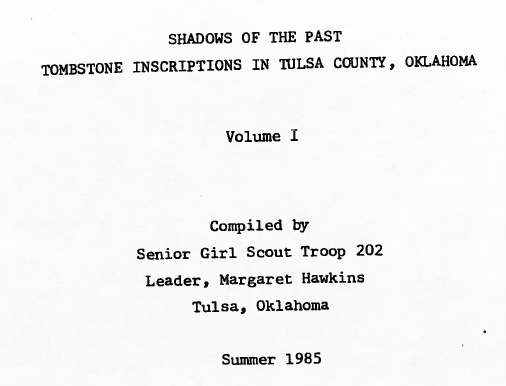

Cemetery records had been maintained, but the 2000 state commission found that no records from Section 20 had been maintained, except for seven veteran burials. It is clear there were records once, as a 1920 interview of the sexton, Thomas Feely, indicated that he had a great spatial memory, but also kept records for each burial. Regardless, we do know that when the City recommissioned the Oaklawn ledger in 1935, the pages for Section 20 were blank. There was a Girl Scout survey of Oaklawn from 1985 which included Section 20, although the location of the markers was somewhat challenging to follow. Our team made a public record request that yielded a marker survey conducted on some unknown date, but since it was an Excel file we think the date is associated with an effort in the late 80s to digitize the cemetery records. This record, which included row and burial numbers, showed that the area was largely unchanged, give or take a sunken flat marker, and was more accurate than the Girl Scout survey. This City survey did not include any indication of where the unmarked graves for the race massacre victims were located.

In 2020, when my colleagues and I started our field investigation of Oaklawn, we started in a location called the Sexton’s area, which oral history had suggested was the location of a trench burial from the massacre. We found that the area was unused. Later inspection of the cemetery ledger indicated that the area was unused! It had been assigned for City use, and the City has yet to use it. As I continued to search for death certificates related to the event (my colleague passed before finding the one historical female victim), I collected the certificates for the marked graves in Section 20 and discovered that the Colored Potters Field had operated as a single grave burial plot. A few family members are buried in proximity, something that can’t be guaranteed in a standard potters field. By combining sparse City records, death certificates, and historical documents including probate records and newspapers, we’ve reconstructed some of the history of use of Section 20, even if we can’t yet place names on most of the burials we have exhumed. Sadly, our mission is to the probable victims we exhume, and the many well-casketed female, juvenile, and infant burials are not exhumed or examined further for identification.

Curiously, we’ve encountered multiple adult male burials with an infant placed on his legs. We’ve had no success connecting infant to the adult male through DNA, and now we wonder if this was a practice of the time that resolved burial costs for stillborn infants. If the funeral services community has any intel, I would love to hear it. These are the only non-single burials we have encountered in the very orderly Section 20.

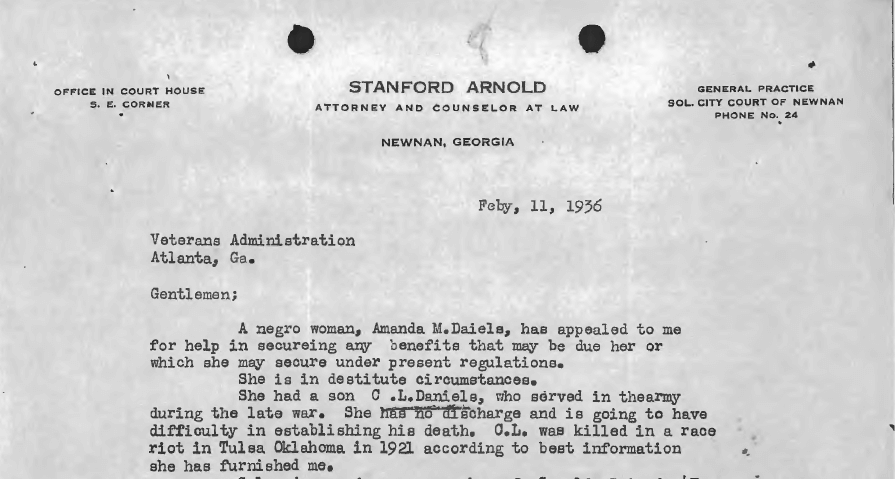

Where are the massacre victims? We have so far identified one victim through genetic genealogy, Private CL Daniel, whose military records revealed his status.

Pvt. Daniel was buried relatively near the markers for Everett and Lockard, strengthening the concept that the twenty males were buried in the same general area, but other graves in that location were clearly not victims. Our excavations to date have revealed neat, orderly rows of generally individual burials, each oriented east-west, with no intrusive or shallow burials. We’ve encountered women in caskets with fancy hardware, and a children’s row, in juxtaposition with our target males in plain caskets. Our first gunshot victim, another feature sought for possible massacre victims, was an adult outlier buried in the children’s row. However, in 2024 we exhumed three males, from the “Original 18” area, who had each been shot with multiple forms of firearms, and one man had also been burned. These three exhibit the mob violence described in the history of the race massacre. Hopefully each will obtain his identity through our genetic genealogy process.

The genealogical process for African Americans is often long, but we continue to wait and hope for families to contribute their genealogies and DNA to the public databases like GedMatch, which will help us connect them to their missing relatives. In the meantime we keep investigating, searching the earth and records to reconstruct the history of this event and bring identity back to these hidden dead.